Neurodiversity, board recruitment and why access still matters

Kicking off our 'Focus on Boardroom Diversity' series, Aurelia Deflandre's first of three pieces on neuroinclusion presents an introduction to neurodiversity, looks at why it is an important consideration for boards and suggests ways in which board recruitment can be made more neuroinclusive.

Date: 4th Feb 2026

Author: Aurelia Deflandre, Director, Neurodiverse Sport

Neurodiversity is a fairly recent concept, only appearing in print in the 1990s, although neurological diversity itself has always been present as part of the normal human experience.

Diversity is now part of the workplace conversation, but in governance spaces it is still often treated as peripheral. Something for HR, for operational teams, or for inclusion strategies that sit alongside “real” board work rather than within it. Much work has been undertaken, through the inclusion of requirements and targets in governance codes and EDI initiatives sponsored by the Sports Councils, among others, to support organisations in their efforts. This has yielded important progress. However, there is still much more to do to ensure that boards are truly reflective of wider society and that thinking around diversity and inclusion goes wider and deeper.

Boards are, by definition, responsible for long-term stewardship, sound decision making, and ethical oversight. The way they recruit, select, and structure participation is not neutral - it determines who gets access to power and whose perspectives shape outcomes. From that standpoint alone, neurodiversity is already a governance issue, whether boards explicitly recognise it or not.

Before we talk about influence, culture, or long-term impact, we need to spend time on the basics: what neurodiversity actually is, why it matters at board level, and how recruitment practices can quietly exclude people long before a board meeting ever takes place.

What neurodiversity means in practice

Neurodiversity refers to the natural variation in how human brains function. It includes differences in attention, sensory processing, communication, memory, emotional regulation, and problem-solving. Autism, ADHD, dyslexia, dyspraxia, Tourette’s syndrome, and many others sit within this umbrella, though not everyone identifies with labels or has a formal diagnosis. There are other words people can use to describe themselves and that should always be respected. The author of this article identifies as neurodivergent and autistic.

Estimates suggest that around 15-20% of the population is neurodivergent. This is not a small or exceptional group. It includes people with a wide range of cognitive profiles, strengths, and support needs, many of whom are already operating at senior levels, often without ever disclosing. Some research suggests that by 2030, 40% of the population will identify as neurodivergent. For organisations, this warrants attention for at least two reasons. First, from an equity point of view, addressing obstacles to neuroinclusion forms part of a culture and approach of recognising differences and understanding the need to enable equality of opportunity for all. Secondly, there is a potentially sizeable risk in business and performance terms in effectively sidelining such a significant section of society, or in not enabling them to give fully of themselves.

For boards, understanding and improving neuroinclusion matter because neurodivergent people are not external to governance systems. They are already present in them, sometimes thriving, often masking, and frequently excluded from opportunities in ways that are difficult to see unless you know what to look for.

With ableism, stigma, judgement and potential discrimination sadly still widespread, it often feels habitual for a neurodivergent person to mask or change their behaviours in public settings, regardless of the challenges they may face by doing this.

Why boards should pay attention

Good governance depends on judgement, challenge, and the ability to hold complexity. It requires boards to look beyond consensus, to interrogate assumptions, and to notice risks before they fully materialise.

Cognitive diversity strengthens all of this. Many neurodivergent people bring strong pattern recognition, systems thinking, long-term focus, ethical sensitivity, and a willingness to question flawed logic. These are not “nice to have” traits; they are directly relevant to effective oversight and decision making.

When boards unintentionally screen out neurodivergent candidates, they narrow their own field of vision. That is not an inclusion problem alone; it is a governance risk.

Where recruitment quietly excludes

Most exclusion at board level does not come from explicit bias but from habit or not challenging the status quo and doing things the way “they’ve always been done”.

Board recruitment often relies on informal networks, unspoken norms, and assumptions about what a “good board member” looks and sounds like. Interviews privilege verbal skills, self-assurance, fluency, confidence under pressure, and rapid responses. Role descriptions can be vague, heavy on cultural fit, and light on what the role actually requires in practice.

These mechanisms reward familiarity rather than capability and favour people who already know how boards operate socially, who are comfortable with ambiguity, and who can perform competence in conventional ways. Neurodivergent candidates, particularly those who communicate differently or need time to process information, are often filtered out at this stage, despite having relevant expertise or governance potential.

This is rarely intentional but intention does not change outcome.

Access is not about lowering standards

There is still an unspoken fear in some governance spaces that making recruitment more accessible means compromising on quality. In reality, accessible recruitment tends to sharpen standards rather than dilute them.

Clear role expectations, structured selection processes, transparent criteria, and flexibility in how candidates demonstrate competence allow boards to focus on what actually matters: independence of thought, sound judgement, strategic insight, and ethical reasoning.

When boards rely on informal signals of confidence or “presence” as proxies for capability, they increase the risk of groupthink and poor challenge. Accessibility, in this sense, is not a concession but a necessary correction.

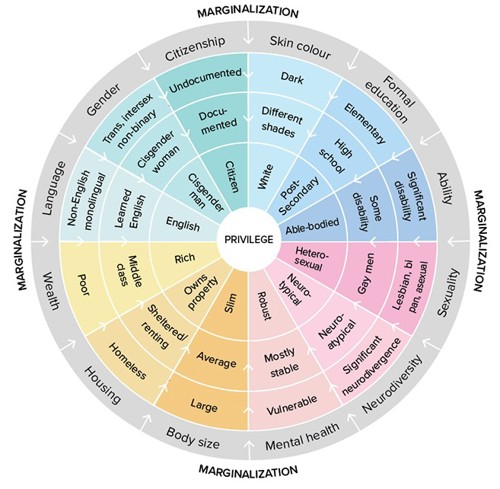

It is important to understand neurodiversity in the broader context of inclusion. First coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989, intersectionality is an analytical framework used for understanding how social identities (e.g. race, gender, class, sexuality, and ability) overlap to create unique, compounded experiences of discrimination or privilege. A neurodivergent candidate who is also from a marginalised racial or gender background will face compounded barriers. Policies that address neuroinclusion must also account for these overlapping identities to be truly effective. By using an intersectional lens, organisations and policies can better address the specific needs of the most marginalised individuals rather than assuming a universal experience for any single identity group.

Wheel of Power

Wheel of Power, Privilege, and Marginalization, by Sylvia Duckworth. Original from the Canadian Council of Refugees (CCR): https://ccrweb.ca/en/anti-oppression

The limits of representation alone

Some boards are now actively seeking neurodivergent candidates, often with good intentions. Without a deeper understanding of neurodiversity, however, this can lead to performative inclusion.

Recruiting a single neurodivergent board member does not automatically create inclusion. It can, in fact, place that individual in a precarious position, particularly if disclosure is expected or if their contribution is quietly confined to “diversity” topics rather than core governance decisions.

Access without structural support creates new risks: reputational vulnerability, isolation, and pressure to conform. These are governance design issues, not individual failings.

Practical Tips

When thinking about your board recruitment process:

|

Why access still matters

Despite these limitations, access remains essential. Without it, influence is impossible.

Boards that take neurodiversity seriously at the recruitment stage are laying the groundwork for better governance later. That means recognising neurodiversity as a legitimate dimension of diversity, understanding that disclosure is complex and often risky, and accepting that difference does not need to be fixed in order to be valuable.

Access is not the end goal. But without it, everything that follows becomes theoretical.

In the next article, we will move beyond recruitment and ask a more uncomfortable question for boards: what actually happens once neurodivergent people are appointed, and why inclusion without influence often results in silence rather than impact.

Aurelia Deflandre is a Senior Client Partner and Neurodiversity Lead at Google Ireland. She also provides professional training and coaching through The Neurodiversity Advantage to help enhance leadership skills through emotional intelligence, improve decision making and increase resilience.

Aurelia is a Director of Neurodiverse Sport. Click below to find out more.

Neurodiverse Sport - find out more